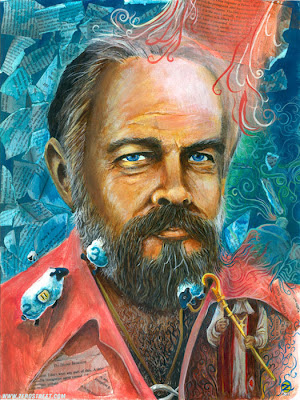

Philip K. Dick: Perbualan Bolano & Fresan

Buku pertama Rodrigo Fresan yang saya baca berjudul Kensington Gardens,

dan pada masa itu, saya belum mengetahui yang dia ialah juga sahabat

baik kepada rakan senegaranya dari Argentina iaitu Cesar Aira (novelis

terbaik di Argentina sekarang), dan penulis yang lebih dikenali di

seluruh dunia, menggantikan reputasi yang pernah dipegang dengan agak

lama oleh Borges dan Cortazar, iaitu Roberto Bolano. Berbeza dengan dua

orang sahabatnya, terutama sekali Aira - walaupun Aira telah menerbitkan

sebanyak tujuh puluh buah novel - Fresan ialah penulis yang kita boleh

katakan prolifik, dan ini boleh dilihat dari jumlah artikel yang

ditulisnya di sebuah majalah Mexico berjudul Letras Libres (ia

diasaskan oleh Octavio Paz); dan seperti kebanyakan penulis generasi

abad kedua puluh satu- sama ada di Amerika Latin atau negara lain -

minat Fresan itu tidak lagi terhad pada urusan "kesusasteraan"

semata-mata, tetapi ia juga merangkumi subjek di luar bidang itu seperti

filem, muzik, dan ada waktunya penulisan berbentuk genre - label

absurd yang masih digunakan oleh penerbit buku - dan antara penulis

yang Fresan, bersama Bolano, minati dalam kelompok ini ialah Philip K.

Dick.

Di

sini saya turunkan kutipan perbualan antara Bolano dan Fresan tentang

Philip K. Dick (kita sudah boleh membayangkan - seperti yang Bolano

ceritakan - perbualan ini berlaku di luar McDonald dengan buku-buku Dick

tersusun di sebelah Big Mac dan Coke):

Rodrigo

Fresán: In recent months I was rereading, and reading for the first time some

of his books, Philip K. Dick, and the first thing that struck me is the fact

that his work has not aged at all, considering he used to say that writing

about what would happen in the coming months, on a future near-present. I think

there are grace and talent: to propose a science-fiction where science does not

matter too much (and is almost always incidental and imperfect, malfunctioning

or not working) and fiction does. I think there is enough evidence now to say

that the idea of our present-future-is much closer to what I thought Dick had argued

than what the classics of the genre did, right? Dick has become a great writer of the

realistic / naturalistic kind, which was what he really always wanted to be before

being forced to make a living writing futuristic novels.

Roberto Bolaño: I remember with great affection Dick. I

think he is the writer of the paranoid, just as Byron was the writer of the

Romantics. Even his biography has certain Byronic nuances: he is always busy and

loving life, and also political, but with lost causes. Sometimes the most extreme cases

or people you think are the most bizarre. And it is curious that one of the

great writers of the twentieth century (something that I think we agree) is

just a "genre" writer. A writer who writes for a living (a horrible term actually) is set to write and publish novels in popular publishing, at a

frenzied pace, novels that run on Mars or in a world where robots are normal

and routine. In short: the worst way to make a name in the world of letters, to

quote a French writer of the late nineteenth century. Yet Dick is not only a famous name in literature but has also becomed a point of reference from other arts

such as film, and his reputation continues to grow. Do you remember the first

novel of his you read? Mine was Ubik and the hammer I received was considerable.

Rodrigo Fresan: True, Dick was very political. He has

something of his own working-class hero not only in the aspect of "working

writer" but many of his stories revolve around working men who are enslaved,

to practice good or bad of a trade, to the dismay of some bureaucracies and

mechanical errors or malfunctions ... In my case the first was The Man in the Castle. I remember I had just returned to Buenos Aires after

a few years living in Caracas, and the effect was disconcerting. It was still governed by

the military dictatorship during 1979 - and I remember it cost a little discerning

where it ended and reality began. The feeling becomes even

greater when read several of Dick's other works: the suspicion that wakes you up on

what is true and what is false. I think it is a suspicion that transcends the

ordinary paranoia and is closer to religious thought. In this sense, I do not

know what you think-I think Dick is the perfect writer for those who do not

believe in God but wish there was some superior intelligence to explain all

this nonsense, right?

Roberto Bolano: Yes, Dick is certainly very much a writer with a

religious concern. There are pages where Dick is clear that he, the author,

would like to believe in God, but there are pages where Dick heard, literally,

the sound of the universe is dying of irremediable. Like Martian Time Slip. A

little music of the spheres beings hear only weakest of the weak and sick

victims. In this sense, Dick never could have been a utopian writer, something

that his writing could have been profoundly moral. Not even dystopias. Dick

writes about Entropy, in capital letters. Curiously, while parallel to this

major issue, run other, more earthlings say, but deeply disturbing, like the

overlapping realities of the Man in the Castle, or his assertion that history, which actually ended in 60 or 70 AD, and everything that has came after are just costumes or virtual reality - and in fact we are living in a total Roman Empire type of universe.

Rodrigo Fresan: Maybe Dick wanted to believe in other planes of

reality, and I venture to think of it as, yes, a necessity and not a conviction, because it

has a much simpler reason, or if you prefer, banal: the option to think that in

another dimension Dick would be a great writer: the writer most important of

all. But perhaps most disturbing of all is Dick's inability to operate within

the parameters of the genre itself. There are well known problems with his colleagues or the fans of science fiction, where they did not understand his

elaborate plots and considered him a sort of drugged terrorist that did not

respect any laws.

Roberto Bolano: No, I do not

think Dick would dream of being the best writer in a parallel dimension to

this. Dick's salvation lies in friendship, sex, shared adventure, not in

writing, much less in what is formally called "good writing" and that it is nothing but a set of conventions accepted by all. However, it is

likely that Dick experienced that sense of clarity about their own writing and

in some moments (moments of weakness and vanity which everyone has) saw as

unjust exile in the literature of genre, the shelf of popular books.

But this is something that has happened to many good writers. In the American

tradition, there are examples where the silence (the case of Emily Dickinson)

or contempt (Melville, for example) are greater than the silence and disdain that Dick sought and experienced.

Kebanyakan penulis tidak suka label. Dan selalunya label yang telah diturunkan oleh sejarah sastera ke atas penulis akan tertanggal (atau dipasangkan semula) dengan sendirinya dari satu generasi pembaca ke generasi seterusnya: misalnya, bolehkah Cervantes terus terkurung dalam sangkar zamannya dan tidak berada dalam kumpulan penulis moden bersama Joyce dan Thomas Mann? atau bolehkah Gogol terus dibaca sebagai penulis aliran fantastik, dan bukan dibaca sebagai penulis pascamoden seperti Etgar Keret? dan bagi yang telah dikenakan label pascamoden - David Foster Wallace, Haruki Murakami, David Mitchell - adakah label itu akan kekal sehingga menyebabkan karya mereka dilhat sebagai permainan pascamoden semata-mata? Untuk penulis kesusasteraan serius - nak sebutnya pun rasa berat - barangkali nasib mereka lebih terjamin, kerana, ya lah, karya mereka sukarang-kurangnya sudah dilihat sebagai teks sastera; berbanding dengan penulis genre (Dick, Lovecraft, Ambrose Bierce, M. R. James, dan entah ramai mana lagi), nilai penghargaan atau penerimaan ini datang - kalau ia datang - dengan lebih lambat, kerana sebelum mereka dapat duduk bersama gergasi-gergasi kesusasteraan, mereka terpaksa dikurung dahulu di dalam penjara di atas sebuah pulau terpencil, jauh dari manusia bertamadun, kerana permainan mereka adalah permainan budak-budak, dan budak-budak tidak boleh dibiarkan lari bertempiaran dalam masyarakat. Tetapi kadang-kadang ada saja orang ingin terus jadi budak-budak - yang inginkan nikmat kebebasan - lalu pergi mencari pulau itu.

Dan apabila mereka pulang, selalunya, mereka tidak akan pulang sebagai orang yang sama.

Comments